Colonial-Era Schools in Yangon: living rooms of Myanmar’s modern history

1704

By Hsu (NPNews) - October 17

Yangon’s streets still whisper the rhythms of the city that the British helped shape: broad avenues, red-brick facades and Victorian porticoes. Tucked among those streets are four schools whose walls and courtyards tell a parallel story—of missionary enterprise, Burmese resistance, and the making of modern Myanmar. Visiting them is like reading a social history in brick and plaster: each building records not only an architectural style but also political moments, alumni who shaped the nation, and the changing relationships between education and power. These are Basic Education High School No. 2 Dagon (Myoma National High School), Basic Education High School No. 1 Dagon (formerly Methodist English High School), Basic Education High School No. 6 Botahtaung (locally known as St. Paul’s), and Basic Education High School (1) Lanmadaw (the former St. John’s College).

Myoma National High School — BEHS No. 2 Dagon (Dagon Township)

The cream-colored building with a five-tiered pyatthat roof rising above its main entrance is among Yangon’s most striking school facades. Myoma was founded in 1920 as a nationalist response to colonial schooling: educated Burmese leaders felt that the British system excluded ordinary people and erased local culture, so they created a parallel “national” school movement—Myoma was one of its earliest successes. The cornerstone for the present building was laid in 1929 and the structure opened in the early 1930s under the guidance of headmaster U Ba Lwin; notable features marry Burmese temple motifs to European building techniques. After independence and the nationalizations of the 1960s the school became BEHS No. 2 Dagon, but the old name and its place in the 1920s nationalist movement remain central to its identity. For history lovers and cultural tourists, Myoma offers a vivid lesson in how education became an engine of Burmese self-assertion.

Methodist English High School — BEHS No. 1 Dagon (Dagon Township)

On another leafy stretch of Dagon sits the asymmetrical Victorian complex that once housed the Methodist English Girls School, later known as Methodist English High School. Founded in the 1880s, the school expanded through the late colonial period and educated generations of Yangon’s daughters—many of whom went on to professional careers and public life in independent Burma. The building and campus reflect missionary schooling patterns typical of the time: English instruction, Western curricula, and ties to the global Methodist network. When the socialist government nationalized private and mission schools in 1965, the institution was folded into the state system and renamed Basic Education High School No. 1 Dagon. Today its colonial main block is protected as part of Yangon’s heritage inventory, an architectural anchor that invites visitors to read the intertwined story of religion, empire and women’s education in Myanmar.

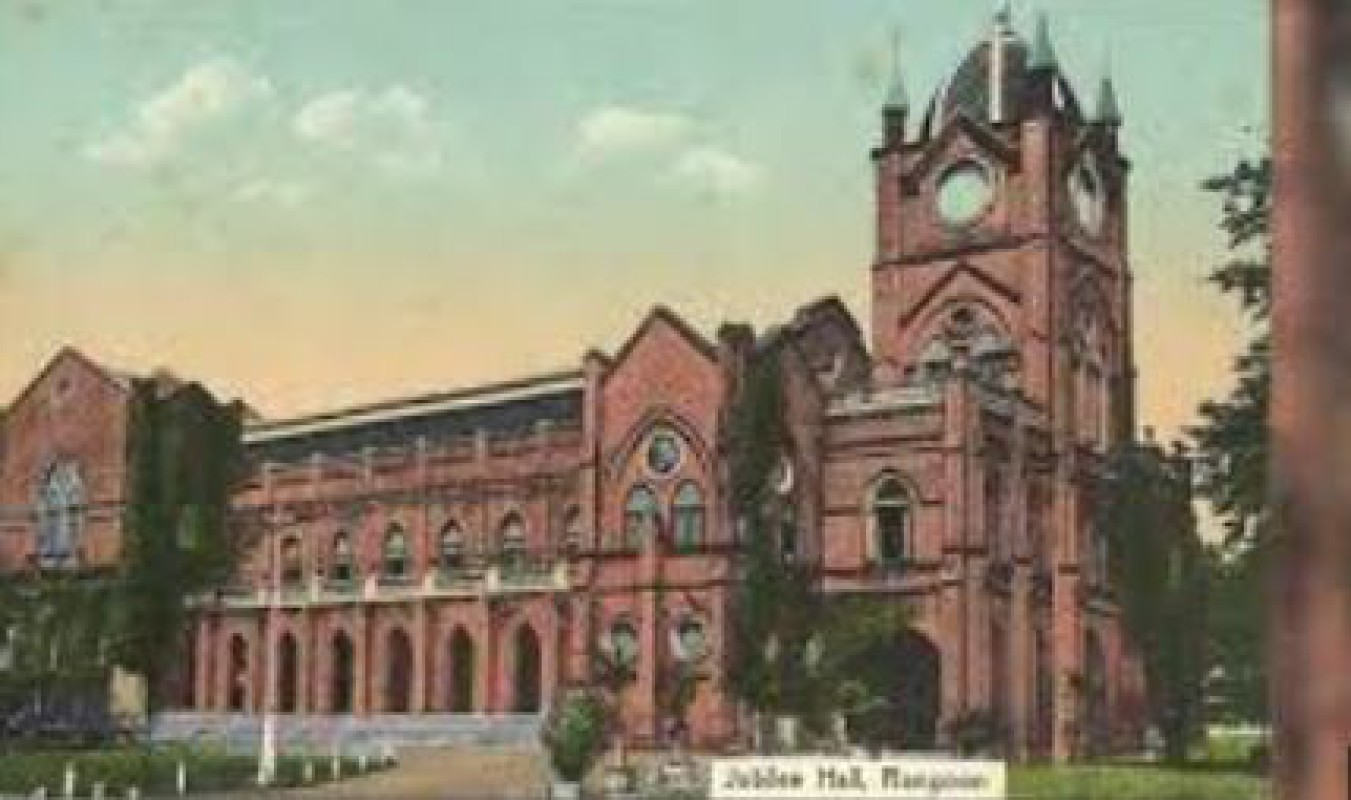

St. Paul’s / BEHS No. 6 Botahtaung (Botahtaung Township)

Red brick and long arched windows make the former St. Paul’s one of Yangon’s best-known school landmarks. Founded by the De La Salle brothers and long associated with Catholic missionary education in the city, St. Paul’s served the European, Anglo-Indian and Burmese families who sought an English-medium education in colonial Rangoon. The building commonly dated to the late 19th century (with various extensions and repairs over time) remains a striking example of colonial school architecture—its scale and layout signal the centrality that mission schools had in the city’s social life. Nationalized in the 1960s and renamed BEHS No. 6 Botahtaung, the site today still carries the informal name “St. Paul’s” among alumni and local residents; the layered identity—missionary past and national present—makes it an evocative stop for international visitors interested in architecture, faith-based education and urban social history.

St. John’s College — BEHS (1) Lanmadaw (Lanmadaw Township)

One of the oldest established Western schools in Rangoon, St. John’s College (later St. John’s Diocesan Boys School) dates to the mid-19th century. It educated multiple generations of Yangon youth and, before nationalization, was a hub of academic and extracurricular life connected to Anglican and diocesan networks. The school building and grounds survived wartime damage and the fluctuations of policy after independence; following nationalization its institution was renamed and integrated into the public school system as BEHS (1) Lanmadaw. Heritage advocates have recognized the building’s historic and urban value, and Yangon’s heritage initiatives have foregrounded St. John’s in lists and blue-plaque programs that invite visitors to explore the city’s missionary and colonial architecture.

For international visitors and heritage travellers

Yangon’s colonial schools are essential stops for anyone wanting to understand how Myanmar’s modern leaders were educated and how civic life was formed. They make excellent additions to heritage walks that already include the Secretariat, City Hall and the colonial docks. Visitors interested in architecture will appreciate the hybrid British-Burmese details at Myoma; those curious about missionary networks will find St. Paul’s and St. John’s rich with archival leads and alumni memories. Importantly, these sites are not frozen relics: they are functioning schools—so visits should be arranged respectfully, ideally through heritage tours, alumni groups, or formal school contacts.

Conservation and the future

Yangon has gradually recognized the value of these school buildings: several are on the Yangon City Heritage List and have received blue-plaque status. That recognition is only a first step. For international scholars, donors and cultural tourists, there are opportunities to support conservation, oral-history projects (recording alumni memories), and careful adaptive reuse that keeps classroom life alive while protecting historic fabric. Partnerships between local preservationists and international institutions can help secure the conservation expertise and funding needed to maintain these living monuments.